Tātai Aho Rau Core Education blog

He kōreroreo, he whakaaro

Discover the latest insights on education and teaching from our blog.

Popular posts

Te Tiriti: how are the Māori and English versions similar?

... Read more >

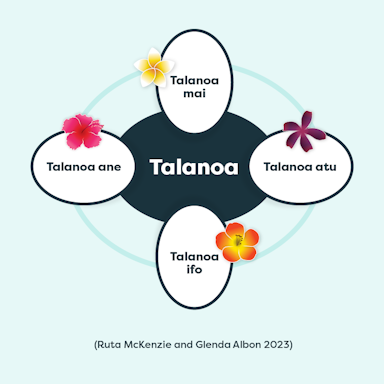

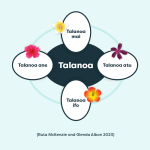

Talanoa is for everyone: a guide for educators

Using the talanoa process enables us to learn more about each other's backgrounds and gives us a better understanding of why we think, feel or act in certain ways.... Read more >

Is your school using Universal Design for Learning - then Te Matāiaho will sound familiar to you!

... Read more >